Methods

Data

Study area

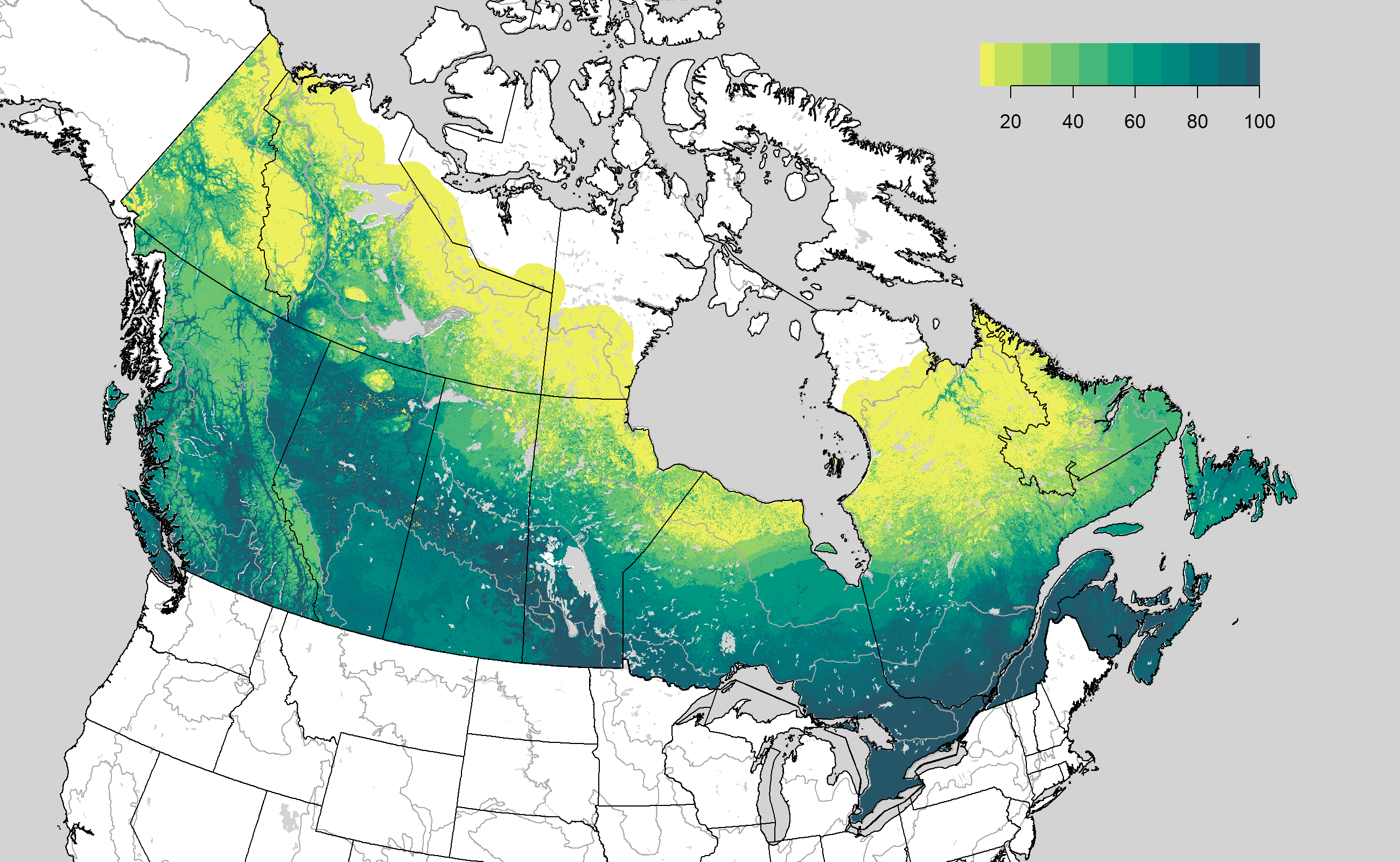

Models were developed based on data from non-arctic portions of Canada. Sampling effort varied greatly across the study area. In general, northern environmental conditions were underrepresented, and southern boreal conditions were overrepresented in comparison with the rest of the study area.

Percentiles of predicted survey effort (number of sites surveyed) based on ~100 environmental covariates and a single boosted regression tree model with a Poisson distribution. Data represent a subsample (1 million 1-km pixels) of the Canadian study area indicated on the map. Mean number of sites surveyed per 1-km pixel = 0.03.

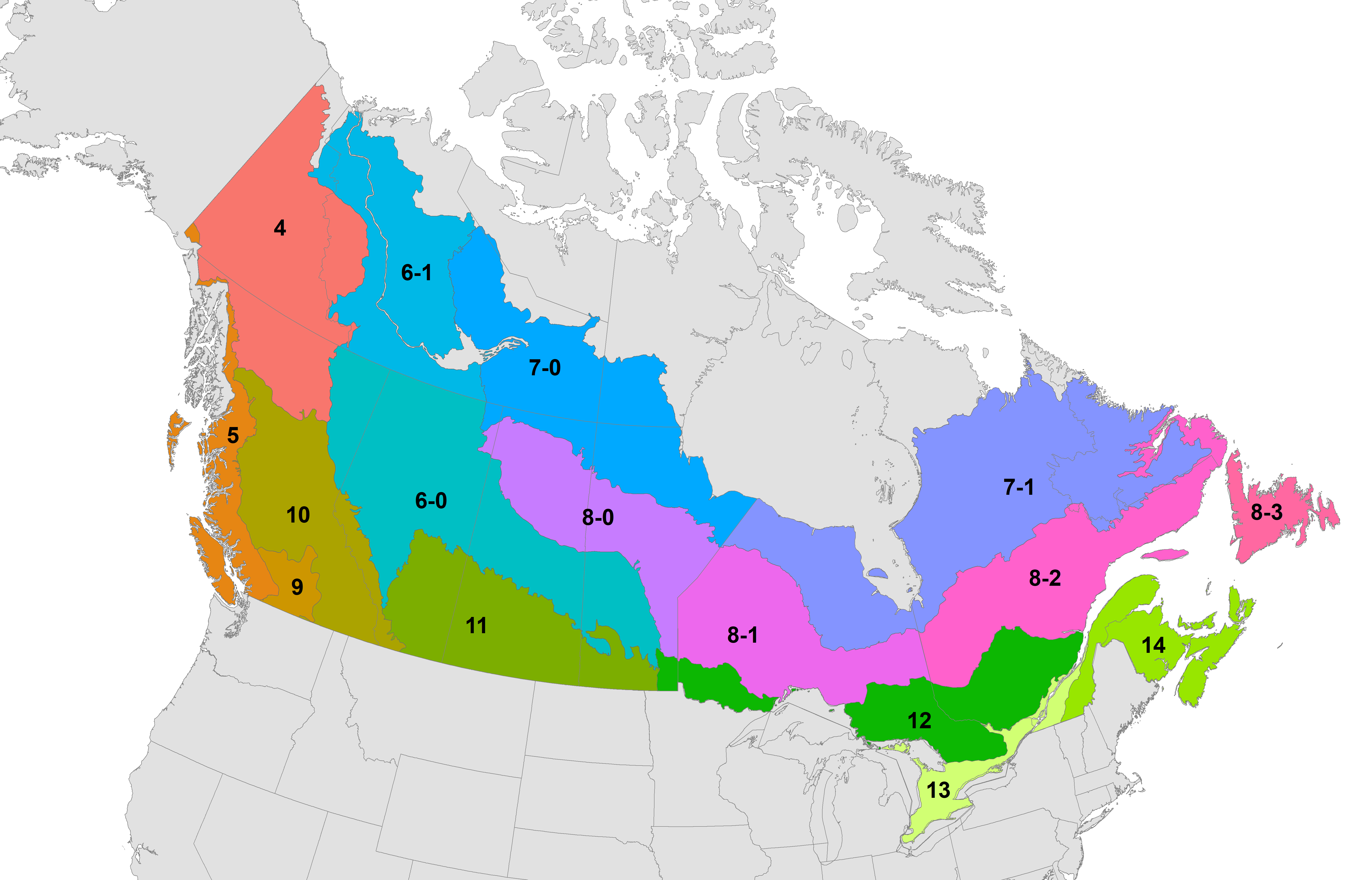

Separate models were constructed for each of 16 separate spatial subunits consisting of bird conservation regions (BCRs) intersected with Canadian jurisdictional boundaries. Smaller BCR x jurisdiction intersections were merged to maintain adequate sample sizes.

Model-building units based on a combination of bird conservation regions and Canadian jurisdiction boundaries.

Model-building units based on a combination of bird conservation regions and Canadian jurisdiction boundaries.

Avian data and subsampling

Avian data were extracted from the BAM avian dataset (v. 4) and supplemented with automated recording unit (ARU) data from the WildTrax acoustic database (6,801 surveys between 2012 and 2018). In total, we sampled data from 296,061 point counts across Canada (across a total of 256,316 site locations and 175 distinct projects). North American Breeding Bird Survey and provincial Breeding Bird Atlas data were included in this database, and constitute a significant fraction of available data (30% and 53% respectively).

We present models for 143 landbird species for which density offsets were available and for which data were sufficient to fit cross-validated BRTs in at least one of the 16 regions. Point-count surveys were conducted between 1991 and 2018 (97% of the point counts were from between 1997 and 2014). We stratified samples by year and geography to produce a more spatially and temporally balanced dataset. We used a 2.5 km x 2.5 km resolution spatial grid to define spatial ‘clusters’ of data. We resampled the data set in each region so that we had a single data point from each cluster/year combination and fit BRTs to the resampled data set. This subsampling addressed instances where multiple visits to the same location occurred within the same year. The subsampling was repeated 32 times.

The list of species is part of the downloadable Excel file.

Environmental covariates

Model inputs consisted of 219 spatially explicit environmental covariates, as well as survey year (continuous) and survey type (binary).

To capture the influence of changing landscape conditions on avian density, we used vegetation maps from 2001 and 2011 (Beaudoin et al. 2014) and associated our survey data with the layer that represented the closest time period. Surveys conducted in 2005 or earlier were associated with the 2001 dataset, while surveys from 2006 and later were associated with the 2011 dataset. Vegetation variables were derived at a 250-m spatial resolution from k-nearest-neighbor (kNN) models that used forest sample plots from Canada’s National Forest Inventory combined with MODIS satellite imagery, as well as climate and terrain data (Beaudoin et al. 2014). Vegetation variables included pixel-level and landscape-level biomass of individual tree species and stand age. Landscape-level covariates were calculated using the focal function in the raster package for R, and were based on a moving-window average using a Gaussian weighting of surrounding pixels (one standard deviation = 750 m).

To capture other sources of landscape variation not represented in vegetation data, we supplemented the biomass and stand age covariates with several terrain, land use, and climate variables. Terrain metrics, calculated using the terrain function in the raster package for R were based on a 100-m digital elevation model for North America. Land-use and landcover variables were based on the 2005 MODIS-based 250-m North American landcover map (Commission for Environmental Cooperation). A binary (0/1) 1-km road variable (Venter et al. 2016) was used to account for the influence of roads at a broad scale. Climate variables were based on a 1-km Climate NA interpolation of 1981-2010 weather station data (Wang et al. 2016).

We pre-screened the environmental predictor variables to eliminate constant (no variation in a BCR subunit) or highly correlated (Pearson’s correlation > 0.9) variables. We also eliminated variables that never entered the cross-validated BRTs to further narrow the variable set for bootstrap to boost computing speed.

The list of covariates is part of the downloadable Excel file.

Analyses

Density calibration, detectability offsets

We accounted for differences in sampling protocol and covariate effects on detectability using statistical offsets. This included the effects of time of day and day of year on the probability of availability given presence, and the effects of tree cover and land-cover type on the probability of detection given availability (Sólymos et al. 2013). Offsets were calculated based on removal and distance-sampling models (Sólymos 2016, Sólymos et al. 2018). These models were used to predict availability and detectability for each species given survey-specific covariates. The adjustments appeared as offsets in the BRTs so that expected values represented species density.

We assumed that ARU detectability is similar to detectability by human observers (Yip et al. 2017). Nevertheless, we used an indicator variable to account for possible differences in effective area sampled between human counts and ARUs following Van Wilgenburg at el. (2017).

Model building

Separate models were constructed for each BCR subunit plus a 100-km buffer around the Canadian portion of the perimeter. We implemented boosted regression tree (BRT) models using the gbm.step function in the dismo R package with a Poisson distribution and 10-fold cross-validation in a preliminary run to assess the number of boosting iterations required to avoid over-fitting. We capped the number of iterations (trees) at 10,000 maximum. BRT settings were as recommended by Elith et al. (2008) and were consistent with Stralberg et al. (2015). We used the number of trees established based on the cross-validation to run models for each bootstrap sample using the gbm function in the gbm R package. This yielded 32 BRT outputs per species and subregions.

We provide information on variable importance for each species by subunits, and for Canada as an average across the subunits (see in the downloadable Excel file). The top ranking variables with respect to variable importance were year of survey, temperature difference, average summer temperature, summer and annual heat/moisture index, and the proportion of developed areas, black spruce, and aspen.

Model validation

We calculated validation metrics using the training data set by making 32 predictions given the bootstrap based BRT outputs. Scale and location shifts across bootstrap based predictions were evaluated by the overall concordance correlation coefficient (OCCC; Lin 1980, Barnhart et al. 2002). OCCC measures the deviation from 1:1 line through the origin, i.e. perfect agreement between two measures. OCCC is the product of two the overall precision (how far each observation deviated from the best fit line), and the overall accuracy (how far the best line deviates from the 1:1 line).

We used the bootstrap averaged predictions to calculate expected values under the null model [exp(initial intercept estimate of the BRT + offsets)] and the final BRT [estimate from all trees combined x exp(offset)]. These initial and final predictions were used to calculate AUC (initial and final) to assess classification accuracy (counts treated as detection / non-detection) and pseudo R2 to quantify the proportion of variance explained (based on Poisson density based deviance relative to the null and saturated models).

Validation results are part of the downloadable Excel file.

Predictive mapping

We used the subregional BRT results to make species and subregion specific predictions using 1 km2 resolution raster layers as predictors. Our predictions represent the expected number of male individuals per ha area given off-road habitat and human observers. We generated 32 predictions for each species x subregion combination. When the actual bootstrap sample did not contain any detections of the species we predicted 0. For each species, we mosaiced together the 16 subregion predictions for a bootstrap run (runs were independent across regions). We varied the width of the overlap zone between subregions (0-100 km) to smooth the predictions at the edges of the subregions and to avoid banded patterns. The random buffer was based on the cumulative density of the Beta(2, 2) distribution. We then averaged the 32 mosaiced layers to get the bootstrap mean of the predictions.